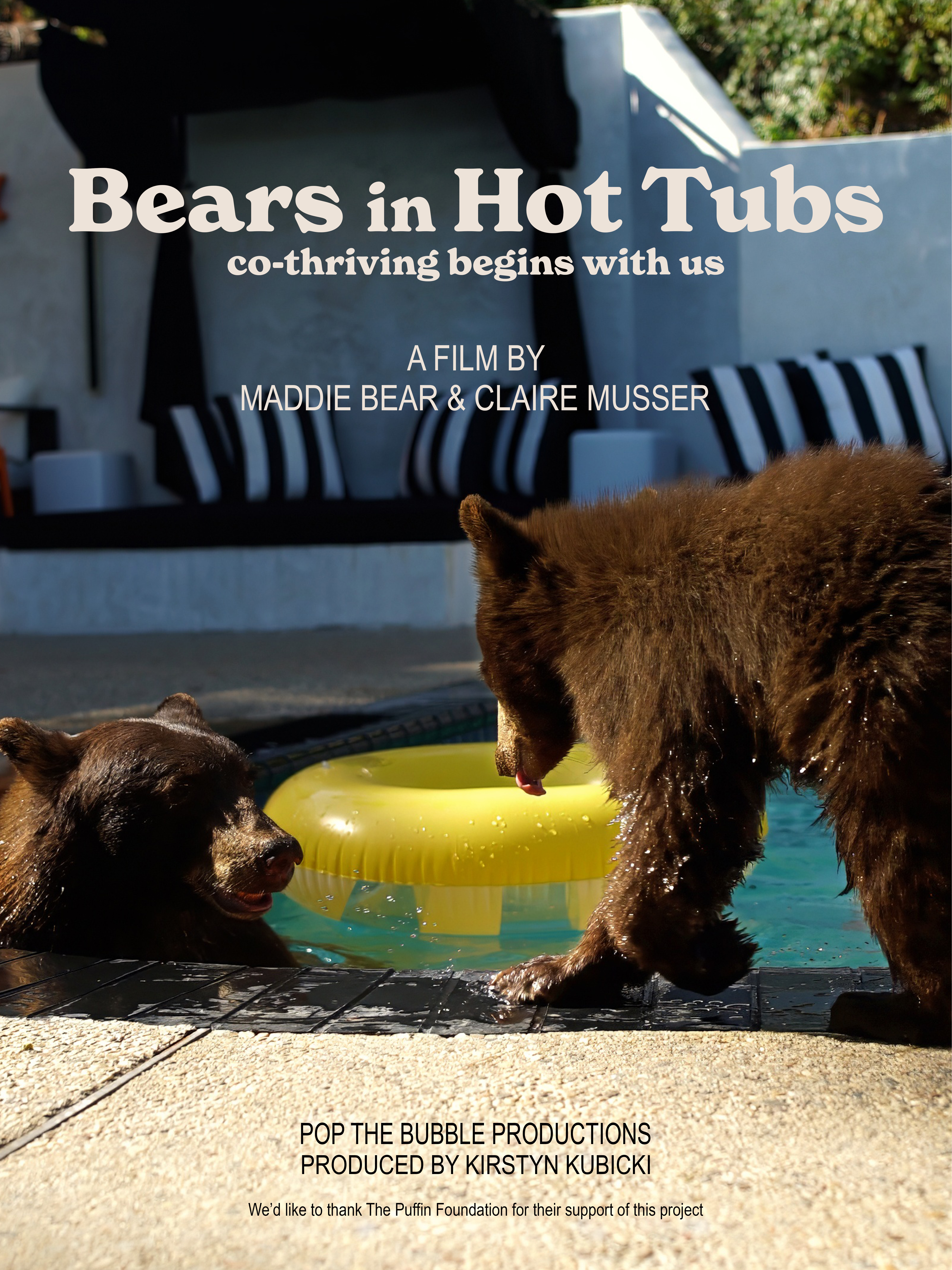

Produced by Kirstyn Kubicki / Pop the Bubble Productions

Film Overview

Bears in Hot Tubs is a tender, emotionally resonant short film co-created with Maddie Bear and her wild kin, who move through the suburban landscapes of Los Angeles with curiosity, intelligence, and quiet grace. From soaking in backyard tubs to wandering garden paths, these black bears are not intruders; they are neighbors, navigating a world remade by human presence.

Rather than depicting wildlife as problems to be solved, the 16-minute film centers the lived experiences of the bears themselves. Maddie shares her world on her own terms, inviting us to witness rather than surveil, to recognize rather than manage.

Through poetic imagery and observational storytelling, Bears in Hot Tubs challenges us to rethink coexistence, not as a burden, but as a shared opportunity. This is a story about boundaries: who draws them, who crosses them, and what it means to co-thrive across species lines.

In a time of ecological uncertainty, the film offers a hopeful reminder: co-thriving begins with us, by listening, adapting, and treating wild lives with empathy, care, and respect.

Director Statement

“When I first saw the footage of bears climbing into a hot tub in suburban Los Angeles, I smiled, and then I paused. There was something more than novelty in their presence: a quiet defiance, a curiosity, a story waiting to be listened to.

Bears in Hot Tubs is not just a film about animals behaving ‘unexpectedly.’ It’s a meditation on what it means to live alongside wildness, what it asks of us, and what it offers in return. As a filmmaker and anthrozoologist, I believe that visual storytelling can shift how we relate to the more-than-human world. But that shift begins with recognition: seeing animals not as intruders or spectacles, but as sentient neighbors navigating the ecological messes we’ve made.

This film was co-created with Maddie and the other bears, whose movements, decisions, and personalities shaped every frame. I chose to work only in spaces where bears expect to be seen, no chase scenes, no interference, because these bears are not subjects. They are collaborators. My role was to wait, watch, and respond with care.

In a time of fire, drought, and displacement, Bears in Hot Tubs offers a small, intimate portal into co-thriving: a practice of mutual presence, humility, and learning. I hope viewers come away not only with affection for these extraordinary bears, but with a renewed sense of responsibility toward the lives entangled with our own.” Claire Musser

Director Biography: Claire Musser

Claire Musser is a filmmaker, environmental photographer, and executive director of the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project. Her PhD research explores co-thriving between humans and wild carnivores through collaborative visual storytelling. Bears in Hot Tubs was co-created with Maddie Bear, of Monrovia, CA, whose presence and participation shaped the film. Claire’s broader work includes field-based coexistence projects with wolves in the Western United States and a forthcoming book chapter, Beyond Coexistence: Co-Thriving with Wolves in the Anthropocene, The Onion Creek Pack and the Legacy of Wolf Persecution (Exeter University Press, 2026).

Producer Biography: Kirstyn Kubicki

Kirstyn Kubicki is an executive producer and creative professional based in Los Angeles. She holds a Master of Arts in Global Management from Thunderbird School of Global Management and has worked across talent management and acquisitions in the entertainment industry. Kirstyn brings a unique blend of business acumen and creative vision to every project she takes on. Her latest work, Bears in Hot Tubs, explores the evolving relationship between black bears and human communities in Southern California. She’s drawn to stories that intersect culture, environment, and narrative, and is committed to amplifying voices and ideas that spark curiosity, compassion, and conversation.

Credits

In collaboration with Maddie Bear & Cubby Bear whose lives made this film possible

Director – Claire Musser

Producer – Kirstyn Kubicki

Editor – Hailee Durant

Illustrator – Chaz Hutton

Associate Producers – Korinna Domingo & Johanna Turner

Director of Photography – Johanna Turner

2nd Unit Directors of Photography – Simon Anderson and Elias Blaset

Drone Operator – Elias Blaset

Fire Footage Drone Operator – Andrew Huang

Music Composer – Madeline Barrett

Music Mixed By – Madeline Barrett and & James Waterman

Sound Designer – Johanna Turner

Assistant Sound Editor – Jordan Mann

Colorist – Jay Jackson

Production Legal – Camille Darko

Archival Footage By: Ernie and Patricia Dunn

Special Thanks To Brian Gordon, Ricardo Martinez, Gail Gottfried, and Brenda Lee

We would like to thank The Puffin Foundation for their support of this project